Siddhartha by Hermann Hesse

As I explore Buddhism to find my new spiritual practice, after God the Father cancelled the Bible in April 2022, I found a goldmine that will give me much to contemplate.

In case YouTube takes down the Siddhartha audio book, I have uploaded it to my private channel.

By

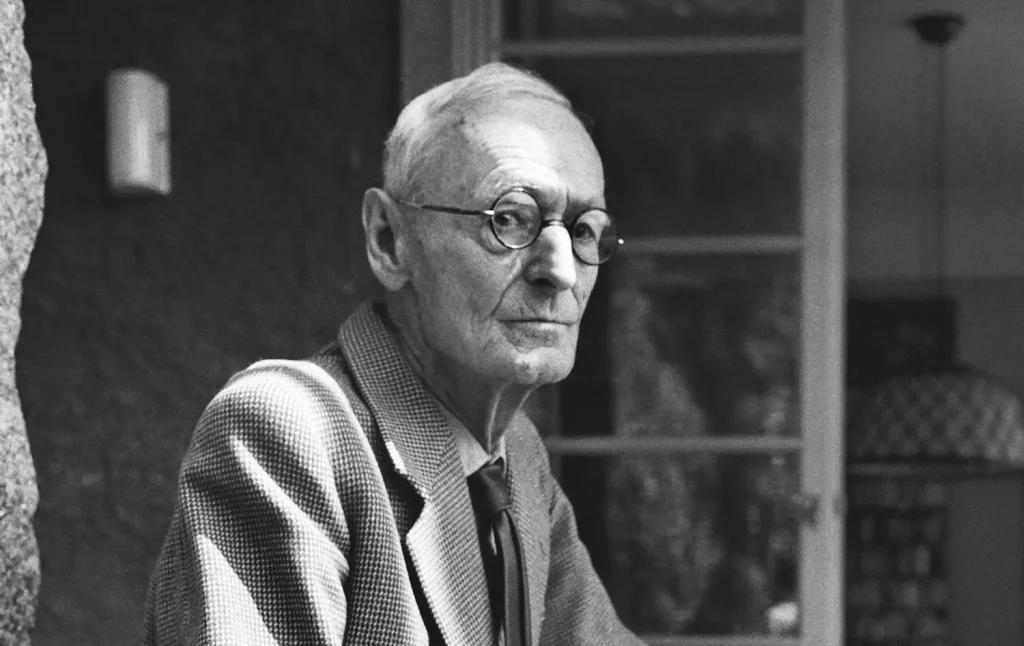

Hermann Hesse (July 2, 1877-August 9, 1962) was a German poet and writer. Known for his emphasis on the spiritual development of the individual, the themes of Hesse’s work are largely reflected in his own life. While popular in his own time, especially in Germany, Hesse became hugely influential worldwide during the 1960s countercultural movement and is now one of the most translated European authors of the 20th century.

Fast Facts: Hermann Hesse

- Full Name: Hermann Karl Hesse

- Known For: Acclaimed novelist and Nobel laureate whose work is known for the individual’s search for self-knowledge and spirituality

- Born: July 2, 1877 in Calw, Württemberg, German Empire

- Parents: Marie Gundert and Johannes Hesse

- Died: August 9, 1962 in Montagnola, Ticino, Switzerland

- Education: Evangelical Theological Seminary of Maulbronn Abbey, Cannstadt Gymnasium, no university degree

- Selected Works: Demian (1919), Siddhartha (1922), Steppenwolf (Der Steppenwolf, 1927), The Glass Bead Game (Das Glasperlenspiel, 1943)

- Honors: Nobel Prize in Literature (1946), Goethe Prize (1946), Pour la Mérite (1954)

- Spouse(s): Maria Bernoulli (1904-1923), Ruth Wenger (1924-1927), Ninon Dolbin (1931-his death)

- Children: Bruno Hesse, Heiner Hesse, Martin Hesse

- Notable Quote: “What could I say to you that would be of value, except that perhaps you seek too much, that as a result of your seeking you cannot find.” (Siddhartha)

Early Life and Education

Hermann Hesse was born in Calw, Germany, a small city in the Black Forest in the southwest of the country. His background was unusually varied; his mother, Marie Gundert, was born in India to missionary parents, a French-Swiss mother and a Swabian German; Hesse’s father, Johannes Hesse, was born in present-day Estonia, then controlled by Russia; he thus belonged to the Baltic German minority and Hermann was at birth a citizen both of Russia and of Germany. Hesse would describe this Estonian background as a powerful influence on him, and early fuel for his inchoate interest in religion.

To add to his complicated background, his life in Calw was interrupted by six years of living in Basel, Switzerland. His father had originally moved to Calw to work at the Calwer Verlagsverein, a publishing house in Calw run by Hermann Gundert, which specialized in theological texts and academic books. Johannes married Gundert’s daughter Marie; the family they started was religious and erudite, oriented towards languages and, thanks to Marie’s father, who had been a missionary in India and who had translated the Bible into Malayalam, fascinated by the East. This interest in eastern religion and philosophy was to have a profound effect on Hesse’s writing.

As early as his very first years, Hesse was willful and difficult for his parents, refusing to obey their rules and expectations. This was particularly true with regard to education. While Hesse was an excellent learner, he was headstrong, impulsive, hypersensitive, and independent. He was raised a Pietist, a branch of Lutheran Christianity that emphasizes the personal relationship with God and the piety and virtue of the individual. He explained that he struggled to fit into the Pietist educational system, which he characterized as “aimed at subduing and breaking the individual personality,” although he later cited his parents’ Pietism as one of the biggest influences on his work.

In 1891 he entered the prestigious Evangelical Theological Seminary of Maulbronn Abbey, where students lived and studied in the beautiful abbey. After a year there, during which he admitted he enjoyed the Latin and Greek translations and did fairly well academically, Hesse escaped the seminary and was found in a field a day later, surprising both school and family. So began a period of tumultuous mental health, during which the adolescent Hesse was sent to multiple institutions. At one point, he bought a revolver and disappeared, leaving a suicide note, although he returned later that day. During this time, he went through serious conflicts with his parents, and his letters at the time show him railing against them, their religion, the establishment, and authority and admitting to physical maladies and depression. Eventually he matriculated at the Gymnasium in Cannstatt (now part of Stuttgart), and despite heavy drinking and continued depression, passed the final exam and graduated in 1893 at age 16. He did not go on to receive a university degree.

Early Work

- Romantic Songs (Romantische Lieder, 1899)

- An Hour After Midnight (Eine Stunde hinter Mitternacht, 1899)

- Hermann Lauscher (Hermann Lauscher, 1900)

- Peter Camenzind (Peter Camenzind, 1904)

Hesse had decided at the age of 12 that he wanted to become a poet. As he admitted years later, once he finished his schooling he struggled to identify how to achieve this dream. Hesse apprenticed at a bookshop, but quit after three days due to continued frustration and depression. Thanks to this truancy, his father refused his request to leave home to start a literary career. Hesse chose instead, very pragmatically, to apprentice with a mechanic at a clock tower factory in Calw, thinking he would have time to work on his literary interests. After a year of the grimy manual labor, Hesse gave up the apprenticeship to apply himself entirely to his literary interests. At the age of 19, he began a new apprenticeship at a bookshop in Tübingen, where in his spare time he discovered the classics of the German Romantics, whose themes of spirituality, aesthetic harmony, and transcendence would influence his later writings. Living in Tübingen, he expressed that he felt his period of depression, hatred, and suicidal thoughts was over at last.

In 1899, Hesse published a tiny volume of poems, Romantic Songs, that remained relatively unnoticed, and even disapproved of by his own mother for its secularism. In 1899 Hesse moved to Basel, where he encountered rich stimuli for his spiritual and artistic life. In 1904, Hesse got his big break: he published the novel Peter Camenzind, which quickly became a huge success. Finally he could make a living as a writer and support a family. He married Maria “Mia” Bernoulli in 1904 and moved to Gaienhofen on Lake Constance, eventually having three sons.

Family and Travel (1904-1914)

- Beneath the Wheel (Unterm Rad, 1906)

- Gertrude (Gertrud, 1910)

- Rosshalde (Roßhalde, 1914)

The young Hesse family set up an almost romantic living situation on the shores of the beautiful Lake Constance, with a half-timbered farmhouse upon which they labored for weeks before it was ready to house them. In these tranquil surroundings, Hesse produced a number of novels, including Beneath the Wheel (Unterm Rad, 1906) and Gertrude (Gertrud, 1910), as well as many short stories and poems. It was during this time that the works of Arthur Schopenhauer were gaining popularity again, and his work renewed Hesse’s interest in theology and the philosophy of India.

Things were finally going Hesse’s way: he was a popular writer thanks to the success of Camenzind, was raising a young family on a good income, and had a wide array of notable and artistic friends, including Stefan Zweig and, more distantly, Thomas Mann. The future looked bright; however, happiness remained elusive, as Hesse’s domestic life was particularly disappointing. It became clear that he and Maria were ill-suited for each other; she was just as moody, strong-willed, and sensitive as he was, but more withdrawn, and hardly interested in his writing. At the same time, Hesse felt he was not ready for marriage; his new responsibilities weighed on him too much, and while he resented Mia for her self-sufficiency, she resented him for his unreliability.

Hesse attempted to ameliorate his unhappiness by giving into his urge to travel. In 1911 Hesse left for a trip to Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Sumatra, Borneo, and Burma. This trip, though undertaken to find spiritual inspiration, left him feeling listless. In 1912 the family relocated to Bern for a change of pace, as Maria felt homesick. Here they had their third son, Martin, but neither his birth nor the move did anything to ameliorate the unhappy marriage.

First World War (1914-1919)

- Knulp (Knulp, 1915)

- Strange News from Another Star (Märchen, 1919)

- Demian (Demian, 1919)

When the First World War broke out, Hesse registered as a volunteer for the army. He was found unfit for combat duty due to an eye condition and the headaches that plagued him ever since his depressive episodes; however, he was assigned to work with those taking care of prisoners of war. Despite this support of the war effort, he remained staunchly pacifist, writing an essay called “O Friends, Not these Sounds” (“O Freunde, nicht diese Töne”), which encouraged fellow intellectuals to resist nationalism and warlike sentiment. This essay saw him for the first time embroiled in political attacks, defamed by the German press, receiving hate letters, and abandoned by old friends.

As if the belligerent turn in his nation’s politics, the violence of the war itself, and the public hatred he experienced were not enough to fray Hesse’s nerves, his son Martin had become ill. His illness made the boy extremely temperamental, and both parents were worn thin, with Maria herself falling into bizarre behavior that would later devolve into schizophrenia. Eventually they decided to put Martin in a foster home to ease tensions. At the same time, the death of Hesse’s father left him with a terrible guilt, and the combination of these events led him into a deep depression.

Hesse sought refuge in psychoanalysis. He was referred to J.B. Lang, one of Carl Jung’s former students, and the therapy was effective enough to allow him to return to Bern after just 12 three-hour sessions. Psychoanalysis was to have an important effect on his life and works. Hesse had learned to adjust to life in ways far healthier than before and had become fascinated by the inner life of the individual. With psychoanalysis Hesse was finally able to find the strength to tear up his roots and leave his marriage, putting his life on a track that would fulfill him both emotionally and artistically.

Separation and Productivity at Casa Camuzzi (1919-1930)

- A Glimpse into Chaos (Blick ins Chaos, 1920)

- Siddhartha (Siddhartha, 1922)

- Steppenwolf (Der Steppenwolf, 1927)

- Narcissus and Goldmund (Narziss und Goldmund, 1930)

When Hesse returned home to Bern in 1919, he had decided to abandon his marriage. Maria had had a severe episode of psychosis, and even after her recovery Hesse decided there was no future with her to be had. They divided the house in Bern, sent the children away to boarding houses, and Hesse moved to Ticino. In May he moved to a castle-like building, called Casa Camuzzi. It was here that he entered into a period of intense productivity, happiness, and excitement. He began to paint, a longtime fascination, and began writing his next major work, “Klingsor’s Last Summer” (“Klingsors Letzter Sommer,” 1919). Although the passionate joy that marked this period ended with that short story, his productivity was undiminished, and in three years he had finished one of his most important novellas, Siddhartha, which had as its central theme Buddhist self-discovery and a rejection of Western philistinism.

In 1923, the same year his marriage was officially dissolved, Hesse dropped his German citizenship and became Swiss. In 1924, he married Ruth Wenger, a Swiss singer. However, the marriage was never stable and ended just a few years later, the same year he published another one of his greatest works, Steppenwolf (1927). Steppenwolf’s main character, Harry Haller (whose initials are of course shared with Hesse), his spiritual crisis, and his sense of not fitting into the bourgeois world reflect Hesse’s own experience.

Remarriage and Second World War (1930-1945)

- Journey to the East (Die Morgenlandfahrt, 1932)

- The Glass Bead Game, also known as Magister Ludi (Das Glasperlenspiel, 1943)

Once he finished the book, however, Hesse turned towards company and married art historian Ninon Dolbin. Their marriage was very happy, and the themes of companionship are represented in Hesse’s next novel, Narcissus and Goldmund (Narziss und Goldmund, 1930), where once again Hesse’s interest in psychoanalysis can be seen. The two left Casa Camuzzi and moved to a house in Montagnola. In 1931 it was there that Hesse began planning his last novel, The Glass Bead Game (Das Glasperlenspiel), which was published in 1943.

Hesse suggested later it was only by working on this piece, which took him a decade, that he managed to survive the rise of Hitler and World War II. Although he maintained a philosophy of detachment, influenced by his interest in Eastern philosophy, and did not actively condone or criticize the Nazi regime, his staunch rejection of them is beyond question. After all, Nazism stood against everything he believed in: practically all of his work centers around the individual, its resistance to authority, and its finding of its own voice in relation to a chorus of others. He had furthermore previously voiced his opposition to anti-Semitism, and his third wife was herself Jewish. He was not the only one to note his conflict with Nazi thought; by the end of the 1930s he was no longer being published in Germany and soon thereafter his work was fully banned.

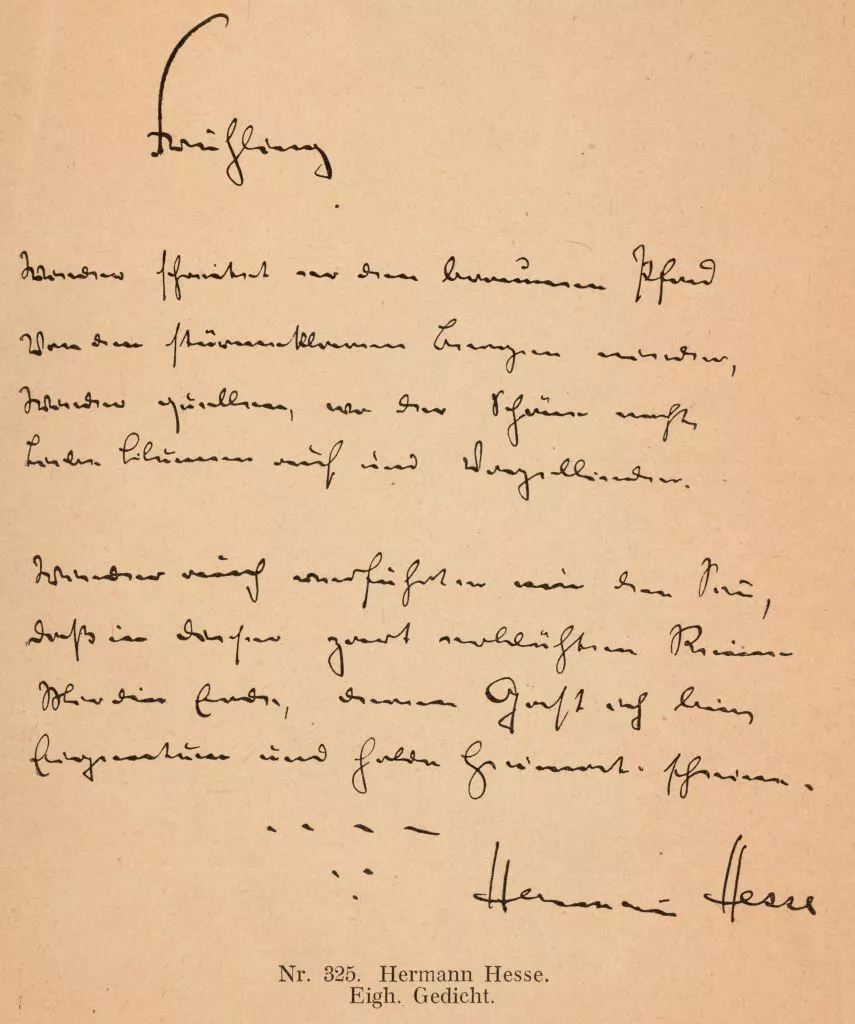

Final Years (1945-1962)

The Nazi opposition to Hesse had no impact on his legacy, of course. In 1946 he won the Nobel Prize in Literature. He spent his final years continuing to paint, writing recollections of his childhood in short story form, poems, and essays, and answering the stream of letters he received from admiring readers. He died on August 9, 1962 at the age of 85 from leukemia and was buried in Montagnola.

Legacy

In his own life, Hesse was well-respected and popular in Germany. Writing during a time of intense upheaval, Hesse’s emphasis on the survival of the self through personal crisis found eager ears in his German audience. However, he was not particularly well-read worldwide, despite his status as Nobel laureate. In the 1960s, Hesse’s work experienced a massive surge in interest in the United States, where it had previously gone mostly unread. Hesse’s themes were of huge appeal to the countercultural movement taking place in the United States and worldwide.

His popularity has been largely maintained since. Hesse has had an effect on pop culture quite explicitly, for example, in the name of rock band Steppenwolf. Hesse remains extremely popular with young people, and it is perhaps this status that sometimes sees him discounted by adults and academics. However, it is undeniable that Hesse’s work, with its emphasis on self-discovery and personal development, has guided generations through tumultuous years both personally and politically, and has a large and valuable influence on the popular imagination of the 20th century West.

Sources

- Mileck, Joseph. Hermann Hesse: Biography and Bibliography. University of California Press, 1977.

- Hermann Hesse’s Arrested Development | The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/11/19/hermann-hesses-arrested-development. Accessed 30 Oct 2019.

- “The Nobel Prize in Literature 1946.” NobelPrize.Org, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1946/hesse/biographical/. Accessed 30 Oct 2019.

- Zeller, Bernhard. The Classic Biography. Peter Owen Publishers, 2005.